Notes for a sermon preached at Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Edmonton, April 28, 2024

Texts: John 15:1-11; 1 John 4:7-12

I spent the summer of 1986 enrolled in Clinical Pastoral Education (C.P.E.) at the Royal Alexandra Hospital. C.P.E. is an intensive program of on-site practice, study, and group work, all under a trained supervisor. I learned a lot in those weeks, including that I was not well-suited to the job of hospital chaplain!

I spent much of my time in those 11 weeks on a long-term medical ward, where it was possible to develop relationships with some of the patients. On the other wards I was assigned, patients were typically only there for a few days. One patient was a man in late-stage cancer. He knew he was dying. During our visits, I came to see that he had accepted what his future held, and I was privileged to be an audience for some of his thoughts about his past life, both positive and negative. I experienced his hospital room as a place of great peace. He had one major regret: while he had come to terms with his prognosis, his wife had not. She was praying continually for his recovery, believing that Jesus would heal his affliction. I only met her once: she arrived during a visit, and told me to leave because I was not of the same faith. A few days later I learned from the staff that he had died. Not long after, I passed a nearby church, where I saw his wife prostrate over the steps, clearly in deep grief.

Why am I telling this story today?

The Gospels for the 5th, 6th and 7th Sundays of Easter are drawn from the Farewell Discourse of John’s Gospel, which runs from the end of the Last Supper in Chapter 13 through Chapters 14 – 17. It begins with Jesus giving the “New Commandment” – ‘Love one another’ – by which everyone will know that they are his disciples.

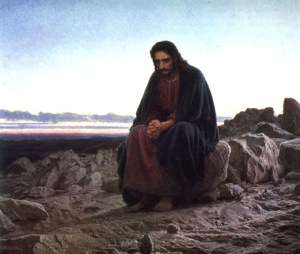

The commandment sets the tone for the rest of the discourse. The central issue is how the disciples are to live without Jesus physically present. Love is to be the rule of their lives, but they will not be on their own. Three times Jesus promises that he will send the Holy Spirit to be with them, to teach them and to be their guide. And three times he promises that he will give them whatever they ask for, if they “abide in [him],” or ask “in my name.” The repetition of these promises indicates just how important they are. The promise of the Spirit is a topic for another day: today we look at the second promise.

The promises in Chapters 14 & 16 refer to asking “in my name.” Quoting those verses out of context can make it sound like a kind of magic spell. Just say “Jesus” and you’ll get what you want! I have heard this kind of thinking from some very well-meaning people, who have said things like, “We didn’t get what we wanted. I guess we didn’t pray hard enough.” As we heard it, the promise in Chapter 15 uses the word “abide,” a word we don’t often hear in this sense in daily speech, but which is found repeatedly in the both the Gospel lection and the reading from 1 John. Other translations have words like “remain”, “live your life”, “joined,” “reside.” Put these alongside “in my name,” and we get some clues about what Jesus means by these promises.

The guiding principle is love. Remember that the first and great commandment is to love God with all your heart, and all your soul, and all your mind, and all your strength. Truly loving God will shape all that we do, all that we say, all that we are, and is reflected in the second: “Love your neighbour as yourself.” The New Commandment Jesus gave is both a repetition and a strengthening of these. Love is our rule because God is love.

Our prayers must always be in the context of love for God and God’s created order (which includes all human beings), under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Prayer is not meant to bend God to our will, but to shape our will to reflect God’s.

One of my favorite sayings about prayer is:

Don’t pray to get what you want;

pray to want what you get.

Another saying is paraphrased from a sermon by St. Augustine on today’s Epistle lesson :

Love God and do whatever you please: for the soul trained in love to God will do nothing to offend the One who is Beloved.

The first part of the quote is sometimes used a bit flippantly to justify the speaker in doing whatever they want, but the clause after the colon makes it clear that seeking to live life in Christ will serve to shape our wills to God’s. That doesn’t mean that every prayer of a faithful person will be answered just as we wish, for our finite human wills are subject to the temptations and trials of this life.

The couple in my story seem to me to point to these two different approaches to prayer. The husband’s prayers were more for those around him, including his wife, asking that they would find the same kind of peace he had found as he neared death. I do not wish to disparage his wife’s faith, but I believe her well-intentioned prayers were rooted more in her own desires and grief than in seeking to know and accept God’s will. I wish I knew how she fared in the time afterwards. I can only pray that she eventually worked through the agony of her grief to find some peace, some kind of acceptance of what had happened for her and her spouse.

Some of you may recall an acronym about prayer, which I first heard in confirmation class: ACTS.

A is for Adoration, spending time in God’s presence, usually without words.

C is for Confession or Contrition, facing our own shortcomings before God.

T is for thanksgiving, praising God for all that we have and all that we are.

S is for Supplication, holding up the needs of others to God, and (finally) for ourselves.

It’s easy to skip one or all of the first three before going on the last. The order is important, because the first three help us to pray as Agnes Sanford said:

The first thing to pray for is the wisdom to know what to pray for.

The first three also help us to put ourselves in a place where we can begin to perceive God’s will, to experience God’s love, and to be able to shape our supplications according to what gives glory to God.

When we pray – however we pray – let us remember that we are not there to dictate to God what God should do. God knows that well enough. Rather, we are called to approach God seeking first to know what God wills, confident in God’s love. And let us remember that hearing comes before speaking.

Let us pray then that through the power of the Holy Spirit, God will open our hearts and minds, that our lives may be shaped more into the likeness of the one who loved us into existence, who loves us today, and who will love us for all eternity.

May it be so.

given for a purpose beyond our own needs. That means that stewardship is very much about money, but before it’s about money, it’s about how we use our treasure to move forward in our participation in God’s mission.

given for a purpose beyond our own needs. That means that stewardship is very much about money, but before it’s about money, it’s about how we use our treasure to move forward in our participation in God’s mission. s beginning, Anglicanism has placed a high value on the public reading of Scripture. Besides being written in English, the first Book of Common Prayer (1549) made some important innovations in worship. Cranmer reduced the multiple monastic daily services to two, the “daily offices” of Morning and Evening Prayer, with the implied expectation that people would participate daily. A system of reading the scriptures (a “lectionary”) was provided for these services, so that anyone who attended them regularly would hear the entire Old Testament every two years, the New Testament three times a year, and the Psalms monthly. While daily attendance at the offices was the exception, the Prayer Book established the centrality of the Scripture in our worship.

s beginning, Anglicanism has placed a high value on the public reading of Scripture. Besides being written in English, the first Book of Common Prayer (1549) made some important innovations in worship. Cranmer reduced the multiple monastic daily services to two, the “daily offices” of Morning and Evening Prayer, with the implied expectation that people would participate daily. A system of reading the scriptures (a “lectionary”) was provided for these services, so that anyone who attended them regularly would hear the entire Old Testament every two years, the New Testament three times a year, and the Psalms monthly. While daily attendance at the offices was the exception, the Prayer Book established the centrality of the Scripture in our worship.