Notes for a sermon preached at St. George’s, Edmonton on July 16, 2017

Texts: Gen 25:19-34; Ps 119:105-112; Rom 8:1-11; Matt 13:1-9, 18-23

Some years ago, I attended a workshop entitled “Unresolvable but Unavoidable Problems in Church Life” led by the Rev. Roy Oswald of the Alban Institute. The title was a pretty good hook, attracting about 200 clergy and lay people from more than 15 denominations. I have since read Roy Oswald’s book, which expands on the workshop’s content. If he’d used the book’s title for the event, I don’t think he would have drawn nearly as many. “Managing Polarities in Congregations” doesn’t have the same buzz, does it? It’s also quite opaque, unless you’re hep to modern management-speak. (What’s a polarity anyway?)

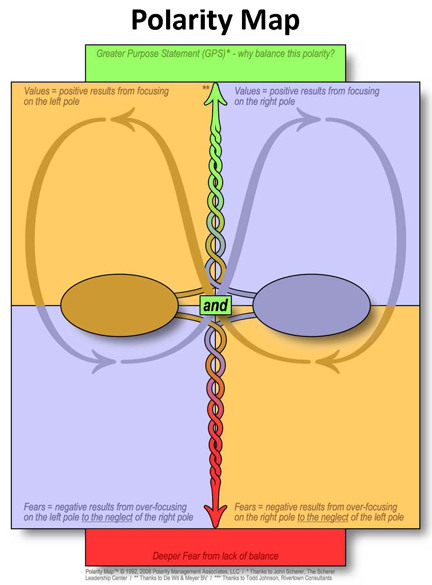

I could quite happily spend a couple of hours or more dealing with this topic and how it applies to church life, but since you didn’t bring bag lunches, I will go straight to the bottom line. There are many situations and issues in life – church, personal, business, government – which are unresolvable because they hold two positive things in tension, which work against each other. We can’t resolve issues like this, but we can learn to live with them.

After attending this workshop, I began to look at life a bit differently. It has been said that if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. In my case, finding polarity management very interesting, I started applying it everywhere. Sometimes it was even appropriate to do so!

Enough theory! Let’s look at the Scriptures. This is one of those Sundays when the prescribed lessons have no obvious linking theme. We heard a story of family conflict, an exhortation to “live in the Spirit,” and the best-known of Jesus’ agricultural parables. I suggest that there is something connecting them. Let’s look at them in turn:

First, Genesis, and the story of Esau selling his birthright for a bowl of lentil stew, or as the KJV puts it, “a mess of pottage.” This is quite a family: parents playing favourites, brothers competing for their parents’ approval, and with each other. Esau is a “manly man,” helping the family by hunting for food. His brother Jacob likes to hang out in the tent, helping his mother with the cooking. By traditional patriarchal standards, Esau should be preferred, but his sly brother tricks him into giving up his rights as elder son: this family’s story will continue through the younger brother. It’s not much of a model for family life. None of its members come off very well; all of them live somewhere on the edge of integrity. They live somewhere in the middle between the ordinary ways of the world and holy righteousness. Nonetheless, God’s chosen people will come from this family.

Second: From Romans, we hear Paul contrasting living according to the flesh with living in the Spirit. “To set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace.” He expands the contrast in Galatians:

Now the works of the flesh are obvious: fornication, impurity, licentiousness, idolatry, sorcery, enmities, strife, jealousy, anger, quarrels, dissensions, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like these. By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Galatians 5:19-21a,22-23a

The choice seems clear: choose the Spirit over the flesh. However, Paul’s assertions that his readers are indeed “in the Spirit” seems to me to be more hopeful than factual. He is telling them what they should be, but surely the truth of most people’s lives is that we struggle with the competing pulls of flesh and Spirit, and live our lives somewhere in the middle, sometimes close to one side, sometimes to the other.

A note here: “flesh” doesn’t just mean things associated with sexual matters. Paul uses it as a generic term for the ways of the present age—the world in which we live. Living “in the flesh” is associating ourselves with things that ultimately do not bring life but death. In contrast, living in the Spirit is living according to the ways of the new age inaugurated through the Resurrection of our Lord. We may know well that this is how we are called to live, but as Paul said in the previous chapter (last Sunday’s lesson), it is all to easy to do the things we do not want, and not do the things we want. Our lives are lived in this ongoing tug-of-war between the ways of this world—the way things are—and the ways of the world to come—the way God wants them to be.

Finally, there’s the parable of the sower, which I have heard re-named “the wasteful farmer.” This man goes out and strews seed without apparent regard for the kind of soil at hand. Much of the seed is wasted, because the soil is beaten down, or rocky, or full of weeds. Only some soil is rich and fertile, bearing grain “some a hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty.” Unlike for other parables, Jesus gives an explanation to his disciples. We can almost hear them saying “We’re the good soil! We will give the good harvest.” Maybe so, but I suspect that those disciples were rather more like most of us. Sometimes we are good soil, and we give a good harvest for the Gospel of Christ, but at other times, we are hampered by the lack of understanding, by the cares of the world, by failing to feed our passion for the Word. The various kinds of soil live within each of us, and thus we live in a constant state of being “between.”

We are both good soil and rocky soil.

We live both in the Spirit and in the flesh.

We live both as people called out by God, and as people experiencing the complications of ordinary life.

We live in the middle.

And yet…

Like Jacob’s troubled family, we are called to build God’s people.

Like the earliest disciples, we are called to be fertile soil for the Word of God.

Like the early saints in Rome, we are called to live into God’s new age, living according to God’s ways.

God knows that we live in the middle—and God still calls us, ready to use us in God’s great mission. God has a purpose for every one of us. May we strive to be aware of our calling, and may we be dedicated to following it, in this world into the next.

Amen.

A good friend and colleague recently disclosed that he had been chosen as one of the four final candidates in an election for Bishop. (Read about it

A good friend and colleague recently disclosed that he had been chosen as one of the four final candidates in an election for Bishop. (Read about it

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.