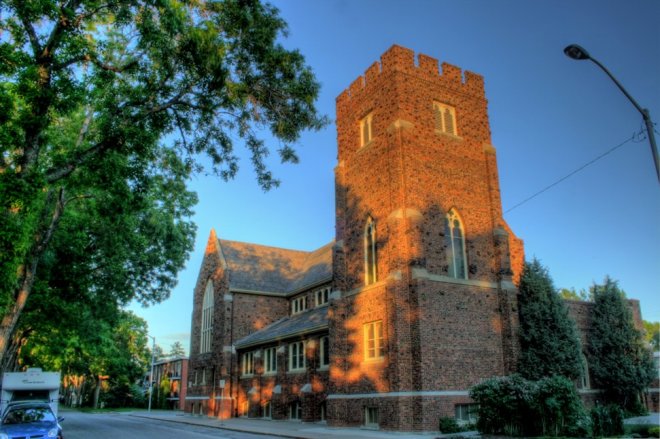

Notes for a Good Friday sermon preached at Holy Trinity Strathcona

Edmonton AB, March 25, 2016

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.

St. Anselm’s simple answer, known as “substitutionary atonement,” was that this was the only way to pay the price for our sin. It has become the dominant answer in much of Western Christianity. The early church did not have the doctrine and the Eastern (Orthodox) churches have never embraced it, but almost every hymn in the Holy Week section of Common Praise shows its influence.

The doctrine found early roots in the High Middle Ages, a troubled and turbulent era, when many theologians emphasized the wretchedness of human existence. Its influence continued into the Protestant churches, finding fertile ground in the teaching of John Calvin and his followers.

It works on a kind of quid pro quo economic system: Everything has a price, so somehow someone has to pay the price of sin.

However—it’s a very troubling doctrine in many ways, depicting God as vengeful, demanding blood sacrifice – of his only Son! Some have called it “divine child abuse.”

Under Anselm’s system, the Incarnation (God taking human form) was necessitated by the need for the cross. Jesus’ ministry was almost by-the-by. Our creeds don’t help us in this respect: both Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds contain “the great comma,” sliding directly from Jesus’ birth to the passion.

As one writer pointed out in a recent blog, the whole thing could have been accomplished much more quickly if Jesus had perished with the Holy Innocents of Bethlehem.

There are other problems, but let’s not spend much time on them. Let’s instead try to look at the death of Jesus of Nazareth through the teaching of another medieval saint – Francis of Assisi, who turned the whole equation around, only a century after Anselm.

Francis held that God’s fundamental act of redemption and salvation was the Incarnation. By entering into human life, God blessed and redeemed all of human existence. God loved humanity enough, that to step into our midst, and pitch his tent among us. And the Incarnation led inevitably to the cross.

What do I mean by that? Simply put: when the Word became flesh in Jesus of Nazareth, “flesh” included and assumed all of human existence. Jesus had to die because Jesus was human – and human beings die.

This human being differed from all others in his pre-existence as the Word (Logos), but as a human being he lived into the failings, all the limitations, all the frailties of ordinary people like you and me.

This human being – God incarnate – came to his own people – and “his own knew him not.” He was rejected by those who should have known him, religious leaders who accused him of blasphemy, people who looked for a human solution to their oppression and found Jesus wanting, leaders of the nation who were prepared to sacrifice one man for his supposed sedition to keep the peace, disciples who were drawn to him but could not hear the fullness of his message.

He was despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity; and as one from whom others hide their faces he was despised, and we held him of no account.

(Isaiah 53:3-4)

He came to bring divine light into this world. “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.” (John 1:5) Jesus came to open the doors to eternal life. And what does that take?

For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. (John 3:16-17)

This is the action of a loving God – who desires that all his people should share his divine life, which is what eternal life means.

Jesus offended the blinded leaders of his nation by his words and actions. He made their lives uncomfortable, making it expedient to have him executed.

Crucifixion makes an example of the offender. It did so in this case, but ultimately not in the way his accusers could ever have imagined. Jesus died as one of us, taking with him to the cross all our triumphs and defeats, all our joys and sorrows, all our gains and all our losses. He died the most shameful death his age could give him. He died a criminal’s death, turning that death into victory, shaming those who wielded the lash and drove the nails, triumphantly proclaiming at the last “It is finished!”

He took the worst the powers of this world could muster against him, and turned it against them through the power of love.

In his birth, in his life, and in his death, God in Jesus took upon himself all that it means to be human.

When we rejoice, remember how Jesus rejoiced over his disciples.

When we weep, remember that Jesus wept at Lazarus’ tomb.

When a child is born, remember that Jesus also was born of a woman.

And when we meet death, remember that Jesus also knew its pains.

Today we remember that God loved us so much that he gave us his Son to lead all people to eternal life. As we look to the cross, let us see not a sign of shame and suffering but the throne of the King of Glory. Our King is crowned with thorns, his face streaked with tears for the people who would not receive him as their king, and handed him over to the powers of this world.

Today and every day, Jesus weeps for us.

Today and every day, let us weep for him and with him.

But finally let us remember that today is not the end of the story. We will tell the next chapter over the great 50 Days of Easter, as we rejoice in the fullness of God’s salvation of the world.

[repeat John 3:16-17]

Thanks be to God!

ion about this before beginning the Eucharist, focussing on the question of why people thought it necessary to remember someone for things that very likely did not happen, glossing over the one solid piece of evidence about his life. Giving a tomb for Jesus’ burial was an act of devotion and generosity that had profound importance in the Gospel story: why can’t we be satisfied with that? Joseph isn’t alone in this. There are other New Testament figures about whom various legends grew up, mostly without solid attestation, often imputing miraculous lives to these individuals.

ion about this before beginning the Eucharist, focussing on the question of why people thought it necessary to remember someone for things that very likely did not happen, glossing over the one solid piece of evidence about his life. Giving a tomb for Jesus’ burial was an act of devotion and generosity that had profound importance in the Gospel story: why can’t we be satisfied with that? Joseph isn’t alone in this. There are other New Testament figures about whom various legends grew up, mostly without solid attestation, often imputing miraculous lives to these individuals.

The church sits uneasily with money. I read of a recent meeting of national staff in which they had concluded that we need a new theology of money. I would agree, but I would drop the word “new”—have we have had any really coherent teaching on this subject? Historical church attitudes to money have veered between the extremes of seeking either great wealth or intentional poverty.

The church sits uneasily with money. I read of a recent meeting of national staff in which they had concluded that we need a new theology of money. I would agree, but I would drop the word “new”—have we have had any really coherent teaching on this subject? Historical church attitudes to money have veered between the extremes of seeking either great wealth or intentional poverty.

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.

Why did Jesus have to die?” is a very common question, arising from believers and sceptics alike.