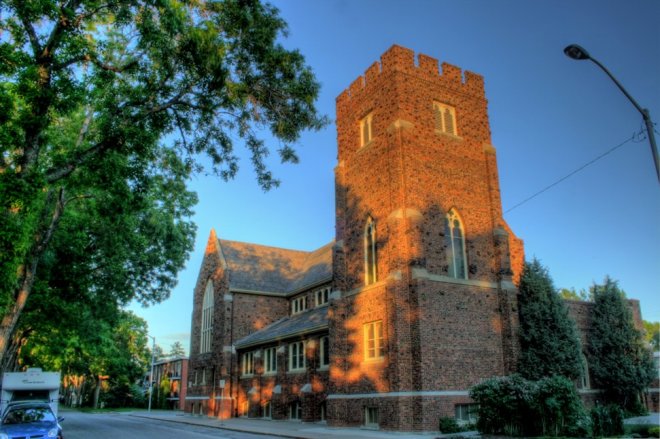

Originally written for “Trinity Today,” the monthly newsletter of Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Old Strathcona, Edmonton, Alberta

As General Synod 2016 approached, Anglicans across the country were invited to study a report entitled “This Holy Estate,” on the question of same-gender marriages. The Thursday morning study group at Holy Trinity Anglican Church spent four weeks in this undertaking. It was an illuminating time for me, not because it changed my perspective on the “big question” (it didn’t much!), but because it showed me just how broad a spectrum of viewpoints could be encompassed in a group of less than ten people, particularly with respect to the Bible and how we read it. None of us in the group read the Bible from a purely literal standpoint, but the place it occupied in our lives was very different, from a profound reverence to near-indifference.

The exercise led me to ponder how we ought to approach the holy Scriptures. I am suggesting that we take a sacramental view of the Bible, which I believe will help to open its words for us to become the living Word of God.

The Sacraments as we understand them have both a material and a spiritual reality: the material both points to and conveys the spiritual. The water of Holy Baptism points beyond itself to the reality of incorporation into the Body of Christ, the Church. The bread and wine of the Holy Eucharist likewise points beyond, to the reality of the presence of Christ in the gathered community and the world around us. In the same way, the words of the Holy Bible lead us beyond the printed page to the reality of God’s presence in humanity and in the world which God created, and ultimately to the redemption of the world through the death and Resurrection of Jesus.

Although Anglican tradition has always placed a high value on Scripture, let it be said here that we do not worship the Bible, but rather the God whom the Bible reveals. The great Anglican theologian Richard Hooker said that the Church – the “called-out” people of God – is founded on scripture, tradition, and reason, which has come to be known as “Hooker’s tripod.” Through the interplay of the three legs, the Church can continue to move forward in its participation in God’s mission. Clearly, Scripture has a foundational and supportive role in this mission.

From it s beginning, Anglicanism has placed a high value on the public reading of Scripture. Besides being written in English, the first Book of Common Prayer (1549) made some important innovations in worship. Cranmer reduced the multiple monastic daily services to two, the “daily offices” of Morning and Evening Prayer, with the implied expectation that people would participate daily. A system of reading the scriptures (a “lectionary”) was provided for these services, so that anyone who attended them regularly would hear the entire Old Testament every two years, the New Testament three times a year, and the Psalms monthly. While daily attendance at the offices was the exception, the Prayer Book established the centrality of the Scripture in our worship.

s beginning, Anglicanism has placed a high value on the public reading of Scripture. Besides being written in English, the first Book of Common Prayer (1549) made some important innovations in worship. Cranmer reduced the multiple monastic daily services to two, the “daily offices” of Morning and Evening Prayer, with the implied expectation that people would participate daily. A system of reading the scriptures (a “lectionary”) was provided for these services, so that anyone who attended them regularly would hear the entire Old Testament every two years, the New Testament three times a year, and the Psalms monthly. While daily attendance at the offices was the exception, the Prayer Book established the centrality of the Scripture in our worship.

More recently, we have come to understand the Eucharist as our church’s central act of worship. While the Sunday lectionary we now use is not nearly as comprehensive as the original daily lectionary, it still places a considerable portion of the Bible before worshipers on a regular basis.

Unlike some other churches of the Reformation, the Anglican church has never defined itself confessionally, by articulating core beliefs to which all members are expected to assent. We have instead tended to define ourselves as a communion through our liturgies. Our worship tells us – and others – who we are. If our worship defines us, it is no stretch to see that the importance of the Bible in our worship also helps to defines us.

So… how do we read the Bible? How do we understand what it is and what it is not? How can it speak to us today without it becoming stale? The Collect of the Day for the Sunday between Nov. 6 & 12 gives some hints about our church’s historical view of Scripture.

Eternal God,

who caused all holy scriptures to be written for our learning,

grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them,

that we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life,

which you have given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ,

who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

(Anglican Church of Canada, Book of Alternative Services, p. 391,

or the Book of Common Prayer, p. 97)

First, it does not say that the Bible is “God’s Word” but rather that God caused it to be written. Fallible human beings put pen to paper to write its many and varied texts, under divine guidance but not as God’s holy puppets. They saw and heard and remembered – and then wrote.

Second, it clearly asserts that the scriptures are to be used. They are given for our learning: “read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest.” How we do this is a matter of personal choice and habit. There is no one right or wrong way for Christians to interact with the Scriptures, except of course, not to do so at all!

Third, we see that our interaction with the scriptures is not a mind game—knowledge for the sake of knowledge—but should lead us beyond the written word to the Incarnate Word. The intended learning should change us. The goal is always a deeper relationship with God in Christ—everlasting life. We are called to become the living Word of God in the world. The Bible is not the end-point of our faith. It is the prime foundational document of the Christian faith, a faith which is not in the Bible but in the one to whom it points.

How do people use Scripture? Sometimes we may sit alone with our Bible in reading or meditation. Very often we hear Scripture proclaimed in the liturgy. At times, we may join in Bible study. In whatever way we interact with Scripture, we are invited to let the words before us change us and draw us ever deeper into a relationship with the One who caused those words to be written. This is truly sacramental – a holy action drawing us closer to God. The Word of God is thus not a static reality on a printed page, but a dynamic reality in the lives of the faithful.

I sometimes preface sermons with this prayer, which I now offer in closing:

Gracious God

Through the written word and the spoken word,

May we become your living Word,

Through him who was and is the Word made flesh,

Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. AMEN.

I am sure that everyone of us would answer this question in differing personal, theological, and spiritual terms. I am no less sure that we here today share something in how we behold the cross. After all, it has been the principal symbol of our faith since the 4th century. We know about Jesus’ death on the cross. We decorate many of our churches with crosses of all descriptions. Some of us make the sign of the cross. Many people wear crosses on their persons.

I am sure that everyone of us would answer this question in differing personal, theological, and spiritual terms. I am no less sure that we here today share something in how we behold the cross. After all, it has been the principal symbol of our faith since the 4th century. We know about Jesus’ death on the cross. We decorate many of our churches with crosses of all descriptions. Some of us make the sign of the cross. Many people wear crosses on their persons.

The church sits uneasily with money. I read of a recent meeting of national staff in which they had concluded that we need a new theology of money. I would agree, but I would drop the word “new”—have we have had any really coherent teaching on this subject? Historical church attitudes to money have veered between the extremes of seeking either great wealth or intentional poverty.

The church sits uneasily with money. I read of a recent meeting of national staff in which they had concluded that we need a new theology of money. I would agree, but I would drop the word “new”—have we have had any really coherent teaching on this subject? Historical church attitudes to money have veered between the extremes of seeking either great wealth or intentional poverty.

Jesus promised “

Jesus promised “

hbour.” Yes!

hbour.” Yes!